By Sonya Woods, Accessibility Consultant with Penn State World Campus

At Penn State World Campus, we want all our students to have a great learning experience. Part of our focus with course design is keeping in mind students with disabilities, whether they are vision-impaired, hearing-impaired, or have cognitive disabilities such as ADHD. And designing to improve accessibility for those students actually improves usability for all students in online courses. Here are four approaches we use to ensure our online courses are accessible.

1. We Conduct Accessibility Testing

We test all the course elements with a screen reader called JAWS (Job Access with Speech). A screen reader is software that enables a computer to read the text on a webpage aloud. JAWS screen reader is favored by people who are blind and is therefore an excellent tool for accessibility testing. If our content works with JAWS, that’s a good sign it will work well for all students, because the design principles that make web content work for screen reader users are good practice for all types of learners.

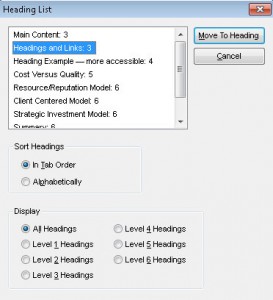

For example, screen reader users navigate by page headings, so we “chunk” our content with headings and subheadings. This not only makes the page navigable for those who can’t see, but it makes it scannable for sighted students and more searchable for everyone.

2. We Follow Best Practices with Accessibility

Designing courses accessibly from the beginning means that all our students, whether they need accommodations or not, have a better experience; if accommodations are needed, very little extra work goes into providing those, allowing us to make the content accessible quickly.

Anytime a course includes a video, we proactively include transcripts, which are accessible for screen reader users, work at low bandwidths, are printable, and are preferred by some students who would rather read the content than watch a video. Providing the content in multiple formats accommodates students with disabilities, students on various devices and platforms, and students with varying learning preferences. Everyone benefits!

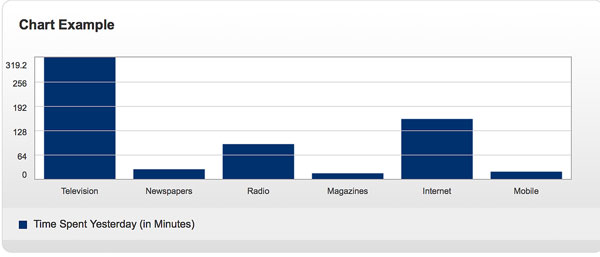

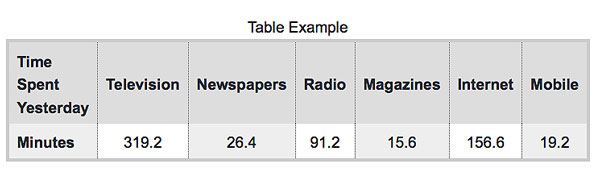

We also offer multiple formats for complex information. Diagrams or charts may have a text description, or the information may also be represented by a table, or a series of lists — whatever communicates the concepts most effectively.

For example, during the summer semester we had a visually impaired student in one of our higher education courses. Part of the course content included a presentation with charts, like this:

To make this information accessible, we also displayed it as a table. The table is accessible to assistive technology, whereas the chart is not.

We not only practice these approaches, but we teach other design staff throughout Penn State about them. My teammate Nikki and I do trainings and presentations for course authors and designers to educate them about accessible course design and universal design principles. Our goal is to help people create learning experiences that work for the widest number of students possible to lessen the need for accommodations.

3. We Research and Use the Best Methods Available

STEM courses (science, technology, engineering, and math) pose some accessibility challenges. A couple years ago, it was common practice to display math content as images in lesson pages. That was a simple way to preserve the complex formatting. These images by themselves were not accessible (because screen readers can’t interpret graphics) and providing accurate alternative text descriptions was challenging as well.

Recently a special code for math content was developed by the W3C Math Working Group called MathML that allows us to display math content in a screen-reader-friendly way. As an added benefit, it’s easily translatable into a number of languages, including Braille. We identified the best way to use MathML with our course creation system and now we use it for all our math content.

One recent success we saw was from a blind student who used JAWS screen reader to complete one of our online math courses. Because we had the content converted into MATHML, he was able to take the course and hear the math content read correctly with JAWS.

4. We Provide Accommodations for Learners with Disabilities

While we do as much as we can to make our course content work for everyone, there is still a need for disability accommodations for some students. When a student with a vision, hearing, or other sensory impairment enrolls in one of our courses, we are notified by Anita Colyer Graham, manager of access at Penn State World Campus, who is notified the Office for Disability Services or Terry Watson, who works directly with students who have disabilities.

When we receive this information, we review the course, looking at course content, materials, and the technologies to identify any potential barriers for the student, and work with the design teams to complete any necessary remediation work. This work can include adding text descriptions to complex images, or providing the information in a more accessible format, such as converting a Word document to an HTML webpage.

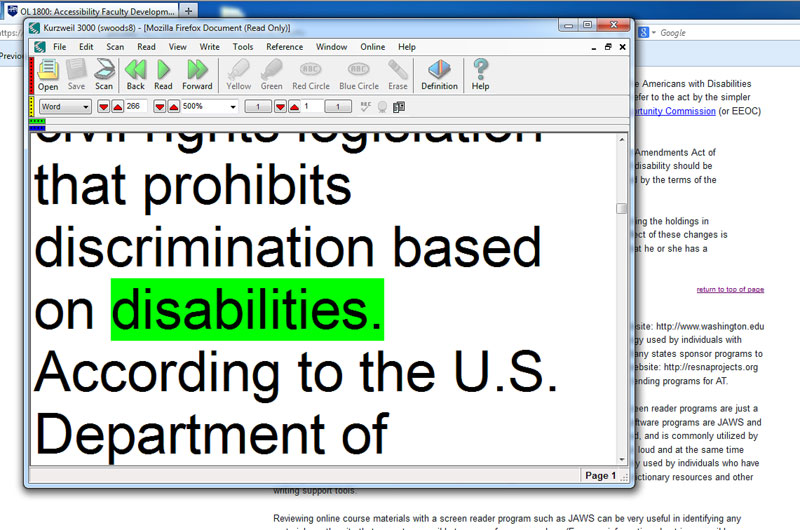

For example, staff from Penn State’s Office for Disabilities Services and the University Libraries make sure course textbooks and readings are provided in an accessible format. Sometimes that means using different software, such as Kurzweil 3000, which magnifies textbooks:

The Future of Accessibility

Technology is always evolving, so our course creation process keeps improving to provide all of our students with better and better learning experiences. While there will always be some need for students with disabilities to receive accommodations, I am hopeful that technology vendors, instructors, and instructional designers will embrace the values in universal design to create products that will work for the widest number of people possible, lessening the need for special accommodations.